You’re half French and half Serbian by origin, you lead a Czech company, and you built the Metropolis project in Bratislava. That’s quite a mix of cultures and experience. What brought you to Bratislava specifically?

From the beginning, I haven’t felt strictly French or Serbian—more European. I’ve always been drawn to travel and discovering other cultures. I’ve loved languages and learned several. What fascinates me most is understanding how people in another country think: their expectations, fears, what they enjoy, what unites different nations, and what sets them apart.

I’ve been living in Prague for 30 years now. I originally went for six months to study at the university. But once I felt the city’s energy and potential—and learned about its history at school—I decided to finish another semester and stay in the Czech Republic. Even though I didn’t end up completing architecture, I chose to work in real estate.

Major cities like Warsaw and Frankfurt have seen a massive construction boom in recent years. Yet you chose Bratislava. Did you consider building Metropolis in other European metropolises?

Definitely not in Germany. We considered entering the Polish market, and I visited Warsaw several times, but the city doesn’t appeal to me personally. From an urban-planning perspective, it stretches along the river and feels inconsistent—you get a modern high-rise, then a prefab block, then something else again. The overall energy in Warsaw just doesn’t draw me in.

Zdroj: Miro Pochyba

Does Bratislava have a better vibe?

It definitely has a better energy, and I feel closer to people in Bratislava and the Czech Republic than to Poles, Hungarians, or others in Central Europe.

Hypothetically. If Bratislava didn’t exist, which European city would you choose for the Metropolis project?

That’s a good question. I’ve thought about it too. I’d probably stay in the Czech Republic, but the project likely wouldn’t happen, since the whole of Prague is under UNESCO protection.

Yes, Bratislava offers more room for growth.

Exactly.

Metropolis has already been approved. How was the building process in Bratislava? What do you see as the biggest differences compared to Prague?

Securing permits isn’t easy, but it’s still simpler than in Prague, where the process is considerably more demanding. Prague is denser, with more buildings—and therefore far more immediate neighbors.

Because the legal framework in the Czech Republic and Slovakia stems from the Austro-Hungarian era and, over the past 20 years, has been layered with EU law, you end up with—on one side—an extremely detailed, dogmatic code, and on the other, a push for freedom that lets almost anything be challenged. In Prague, we have a project that’s been blocked for seven years because a very smart, well-educated politician has made it his political gambit to “stop the bad developers.”

Source: Miro Pochyba

Is the clientele in Slovakia more demanding than in the Czech Republic?

I think the clientele is more knowledgeable than in the Czech Republic when it comes to technology and how to use it. Czechs are much more conservative—more German in outlook. They place less emphasis on new technologies, new trends, and the aesthetic side of products, fashion, or housing.

Are Slovaks more demanding in this regard?

They’re significantly more demanding in this regard. Czechs take a conservative, analytical view of where they put their money.

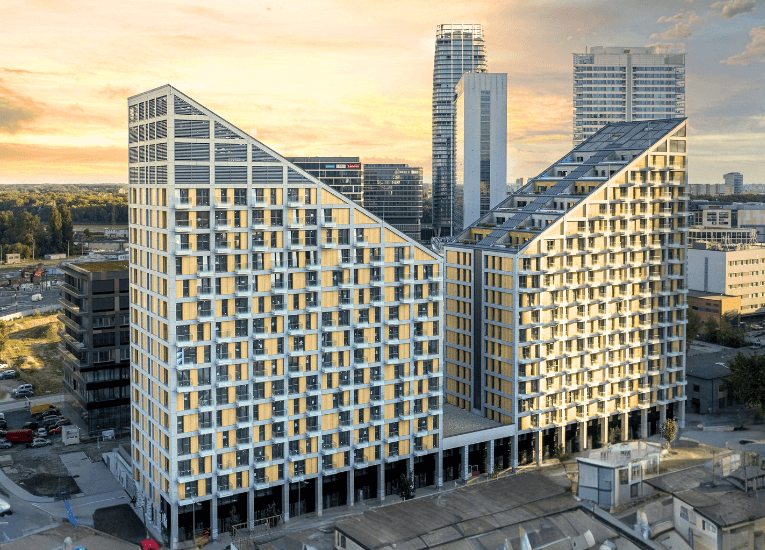

Metropolis rose among 100-meter towers. It isn’t the largest, but it stands out differently—through its bold architecture and distinctive design. Its form evokes the letter “M.” Was that intended to reference the initial of your company, Mint Investments?

We’re developers, not architects. The entire downtown district had a regulatory plan that set the technical parameters for each building, height, floor area, and maximum site coverage for each plot. Architect Juraj Sonlajtner proposed a building shaped like the letter “M.” He met all our requirements while giving the project its envelope and aesthetic so it would appeal to both him and us. He didn’t choose the “M” shape because our company’s name starts with M.

You entered the project nearly twenty years ago. Why did it take so long for Metropolis to actually get underway?

We joined the project in 2007, investing capital from a major U.S. fund. The project then lay dormant for a long time because the district sat within a much broader context.

An urban planning study was being developed, and so on…

Exactly. On one side of the Nivy bus station, you had the developer HB Reavis, then JTRE, and on the opposite side, Penta owned the land. But the city hadn’t completed its traffic study—how transport should operate and who would finance which investments so that the downtown could function. As a result, permits couldn’t be obtained during that period.

So the major developers had to reach an agreement first, and only then could you, as the investor, move forward with Metropolis?

Yes. Ultimately, we acquired the Metropolis project because we saw potential, not risk. The right moment came between 2017 and 2020, as downtown’s urban transformation got underway.

The construction of Metropolis wasn’t entirely smooth. You faced COVID-19, a financial crisis, and the war in Ukraine. Did you ever think, at any point, that you should have sold the project before breaking ground?

Maybe. If you’re a developer. We’re not just developers; we’re fully invested owners. It’s on us how well we prepare, whether we grasp the big trends, and what a potential buyer will be looking for in this product a few years from now. Those are the aspects we can control and plan for.

But we can’t control external shocks—the pandemic or a crisis. Almost everything that could happen did. Then it’s on us: how much we believe in our vision, how we hedge or price in risk, and how aggressively we choose to be. We bought the land with our own capital, without bank financing. Had we taken on bank debt, the situation would have been far more stressful.

We have plenty of development experience. We know plans don’t always work out. As I mentioned, we have a 400-apartment project that’s been tied up in court in Prague for seven years. It’s a bit like BASE jumping. That’s why we don’t do only development—otherwise we’d be far more stressed, and I’d have even less hair on my head than I do today.

As we’ve said, Metropolis has been approved, and the first residents have moved in. It was meant to happen sooner—you announced the occupancy permit for July 2024, with move-ins slated for autumn 2024. Setting aside the events you mentioned, why was the project delayed?

The project was delayed because development isn’t an exact science. Over 3.5 years, the contractor faced high inflation and supply shortages, and we had to agree on increased construction costs. All of that impacts a build from day one.

We were uncompromising about achieving a set standard and refused to lower the bar. The building’s technical and technological complexity—including the materials—brought certain challenges. But we didn’t want to deviate from our goal, so the completion timeline had to be extended.

Our philosophy is that it’s better not to take shortcuts—you have to take the harder path. You’ll reach the goal more successfully if you proceed step by step and never compromise on your principles.

You enlisted well-known Slovak presenter Sajfa to showcase the project. Is he meant to represent Metropolis’s target audience—more affluent, well-educated buyers?

In this project, we wanted to take a slightly different path, not only in architectural and technical solutions. We wanted Metropolis to be different as a product overall. With other products, it’s now standard to use influencers. In fashion, it’s no longer about famous supermodels, but Instagram personalities and influencers.

So we decided to take that route as well. We looked at well-known influencers in Slovakia. As you said, we wanted someone who could represent our product and resonate with potential buyers. For us, Sajfa was the only choice. It took some time to convince him. He’s extremely entertaining—but above all, he’s smart.

He’s an investor himself, and there are people in his family who are passionate about development and real estate investing. He’s a family man, and we share many values. I can’t imagine another influencer who could represent Metropolis better.

Which target groups are moving into Metropolis—who actually live there now?

They’re people who value their time, live intensely, work hard, and want their homes to match their expectations, to suit a fast-paced life. They want to live close to the city center.

Do cash buyers or mortgage-financed buyers dominate? How many apartments have been sold in Metropolis to date?

We’re nearing 80% sold. I’d say the split between mortgage-financed buyers and others is roughly 50/50. Most of the sold apartments have already been handed over—residents are either living there, leasing them to their own tenants, or finishing their interior fit-outs.

As for the retail units, we chose the sales route, and we’re also at roughly 80%. None has been handed over yet. Another factor is timing: for a shop, it makes sense to open either in spring or in winter. Right now, it’s summer.

Aren’t you concerned that your project sits very close to major shopping centers? Nivy is just a few meters from Metropolis, with Eurovea next door. Do you still expect strong sales of the retail units, given this competition?

That’s a good point. We look at the whole district as one city. Large shopping centers tend to offer a certain mix—fashion, restaurants, entertainment, and cinemas. Our project is for people who live fast, and like residents of the neighboring developments, they need a different kind of service.

Do you know what service they want?

We know that, and we’ve chosen buyers for these units accordingly. They fall into two categories: food and beverage—either for on-site consumption or for purchasing high-quality ingredients. Healthcare is also important. We’re living in a time of prosperity; even if many of us don’t realize it and keep complaining about the economic, geopolitical, and political situation, the reality is that in Bratislava, Prague, and elsewhere in Europe, we’ve never had it so good.

It’s evident in how much more time people devote to self-care—how we look, what we eat, what we drink. Our retail strategy reflects that: we’re not trying to replace the big malls; we’re complementing them with services you won’t find there.

Another key topic is the standard of your apartments. They’re not the cheapest, but they reflect a certain level of quality. That said, other downtown projects offer similarly high-quality units. So my question is: what does Metropolis have that, for example, Eurovea Tower or the Zaha Hadid towers don’t—and that Skypark Tower or Ganz House won’t have?

We approach development because we genuinely enjoy it. I drew on my own experience of what luxury truly means. For us, real luxury is the level of everyday comfort you have—both in the apartment and across the project. We chose materials I use at home myself: not the priciest or the most ostentatious, but genuinely high-quality and visually refined.

Another point: we’ve invested heavily in technology—not because it’s trendy or sounds good, but because integrating these systems delivers a level of comfort you can’t get anywhere else.

What kind of comfort is that?

First, cooling the healthy way—via the ceiling. It uses proven German technology that’s been around for 50 years, keeping you comfortable in summer without an AC unit blowing on you. The apartments also feature ventilation with heat recovery (MVHR), ensuring exceptionally clean indoor air. Control of all these systems, including external shading, is integrated.

With the large windows, apartments would get genuinely hot in summer, and you could run the AC endlessly. But when you integrate these three technologies, you get a living experience you simply can’t replicate anywhere else.

What also matters is not only using the right technologies from reputable suppliers, but choosing the right materials. For the visible finishes, we opted for luxurious—though not the most expensive- options, and we put great emphasis on thermal and acoustic insulation. When you’re in the apartment with the window open, you hear traffic, you’re close to a bridge, and there’s a lot of noise. Close the windows, and you hear nothing. That is luxury. We built this project so that nothing will need changing for at least one generation—perhaps not even for the next.

So Metropolis is a two-generation project?

At least. And you’ll see it reflected in apartment values when someone tries to sell. I expect liquidity will be low: once a family buys an apartment, they’ll keep it and pass it on to the next generation.

Metropolis is just one piece of a larger puzzle. In its immediate vicinity, other major players are already planning new developments. Aren’t you concerned that Metropolis residents will lose their privacy?

That’s an interesting perspective, but I think it’s a distinctly Central European one: a desire to stay hidden. It may be a legacy of the communist era. In the Nordics, or in the Netherlands, for example, you see everything open and transparent.

When you look at the B&G studio, you can see they experiment with tower concepts that blend work and living. In that interconnectedness and transparency, people tend to feel better. The project reflects the local mindset. You don’t lose privacy there. Metropolis isn’t as open as some of the projects I’ve seen in Copenhagen. There, architecture introduces a degree of transparency while still allowing residents to shut it out—so they can live in complete privacy if they wish.

Let’s wrap up our discussion of Metropolis. How much did it cost?

The total investment exceeds €62 million.

Have these costs risen compared with your initial estimates and assumptions, in light of what we’ve discussed?

They increased for several reasons. First, we decided to raise the project’s standard. Costs then rose further after the Russian invasion, which drove high inflation and higher interest rates.

What are your company’s plans for Bratislava going forward?

We’re very proud to have delivered a project that will be an integral part and calling card of the downtown. As I mentioned, we’re not just developers—our philosophy for over 20 years has been to invest our own capital and our investors’ money where we see the best returns relative to the risks we take.

We’re not closing the door to further developments—we’ll stick to our philosophy. For now, we believe it’s better to acquire existing buildings—mainly office properties in Prague—or buy blocks of apartments to rent out.

Gen Z is changing how people think: they want to own less and rent more. I believe that shift will reach Bratislava and Slovakia as well. We track megatrends and will adjust our investment strategy to deliver what the market needs.

Are you interested in other parts of Slovakia as well?

Certainly. Eighteen years ago, we built the Laugaricio shopping center in Trenčín. At that time, retail was attractive because shopping malls were virtually absent in Central Europe, and nothing like that was being built. It was an opportunity, so we surveyed the entire western part of Slovakia, the area close to the Czech border, because it made strong sense for a shopping center.

Our ASB editorial team has confirmed that Portum Towers—Metropolis’s neighbor—is up for sale. Are you considering acquiring it?

We looked at the project, but acquiring a permitted scheme with its image, scale, and architecture already crystallized… Since we’re not a large developer, our aim isn’t to have hundreds of units for sale every year. When we take on development, it’s something very personal.

We put our emotions into it—perhaps the only part of the business where emotion belongs—because here we invest our own capital, unlike Mint’s other business lines that involve outside investors. The projects have to excite us. When you buy a scheme that already has a building permit, the entire creative phase—the part I personally enjoy most—falls away. That’s why we didn’t consider acquiring this project.

Sebastien Dejanovski (52)

Sebastien Dejanovski is a partner at the Czech-Slovak investment and development group Mint Investments, where, since 2010, he has played a key role in shaping strategy and managing major real-estate projects. With 20+ years of experience in real estate investment and development, he is recognized as one of the industry’s leaders in the Czech and Slovak markets. For his leadership and strategic vision, he has received awards such as the CIJ Awards and ranks among the 100 most influential real-estate leaders in CEE.

Source: asb.sk

Metropolis: A Symbol of Modern Bratislava

Metropolis: A Symbol of Modern Bratislava

Top New Development of the Year? The Winner Is Metropolis in Bratislava

Top New Development of the Year? The Winner Is Metropolis in Bratislava

Bratislava as a Central European gem, where Metropolis offers a luxurious and secure home, a reliable investment, a prime address, healthy living and modern technologies.

Bratislava as a Central European gem, where Metropolis offers a luxurious and secure home, a reliable investment, a prime address, healthy living and modern technologies.

Family Living in Bratislava’s New Downtown? Buying an Apartment Pays Off More Than Renting

Family Living in Bratislava’s New Downtown? Buying an Apartment Pays Off More Than Renting

Sebastien Dejanovski: Sajfa Represents Metropolis Buyers, and We’re Open to Further Investment in Bratislava

Sebastien Dejanovski: Sajfa Represents Metropolis Buyers, and We’re Open to Further Investment in Bratislava

Ceiling Cooling: Invisible Comfort You'll Fall in Love With

Ceiling Cooling: Invisible Comfort You'll Fall in Love With

Metropolis was built with the same care and vision as if we were building it for ourselves.

Metropolis was built with the same care and vision as if we were building it for ourselves.

Luxury Worth €60 Million: Only 20% of Apartments Still Available in Bratislava's Metropolis

Luxury Worth €60 Million: Only 20% of Apartments Still Available in Bratislava's Metropolis